Since its creation in 1886, it wasn’t long before the idea of racing motor cars caught on. The first European races were held on public roads and would see the pioneering drivers of the day racing at speed between two main European capitals. These continued until the early 20th century, where the notorious Paris to Madrid race of 1903 saw the death of five drivers and spectators.

This led to the creation of the first ever Grand Prix in 1906. Held on a section of closed roads outside Le Mans, it saw the big manufacturers battle it out over two days on a specially designed circuit. The winner was Francois Sisz in a Renault.

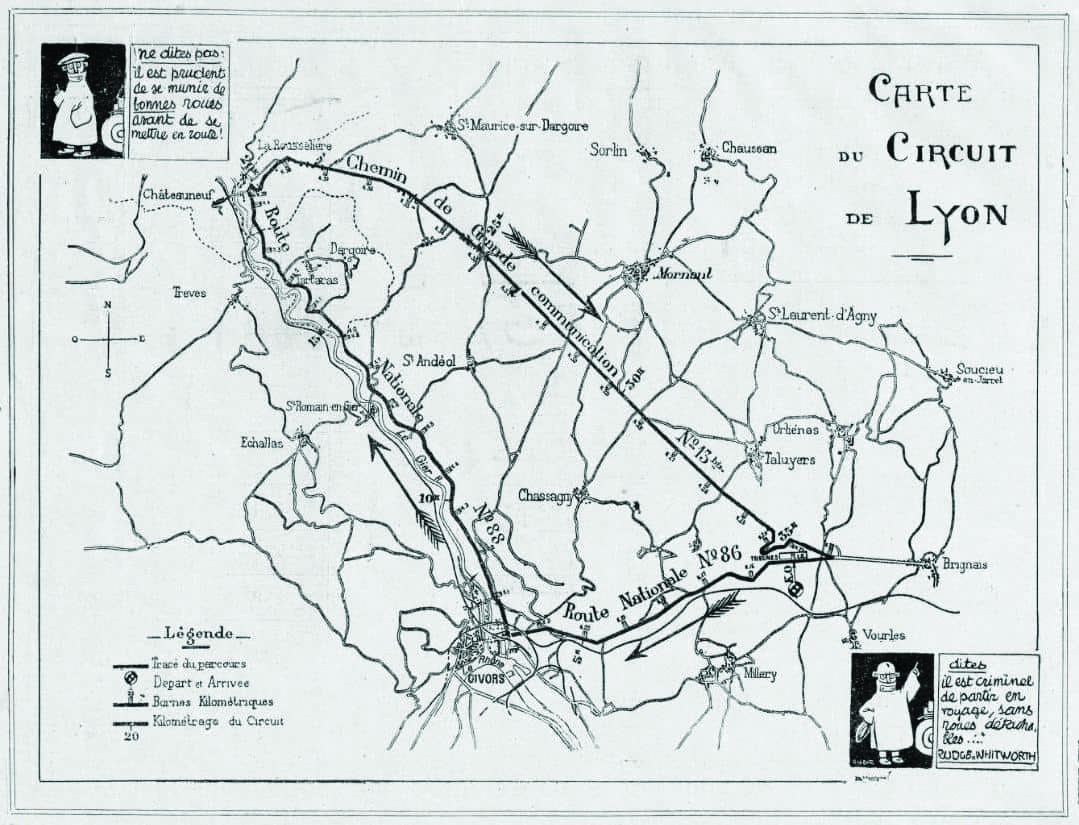

In the years that followed, Grand Prix racing grew immensely in popularity. It became a source of national pride and saw England, France, Italy and Germany all competing for glory. One earlier Grand Prix often described by motorsport historians as one of the greatest ever, took place at Lyon on July 4th 1914, only weeks before the outbreak of World War I.

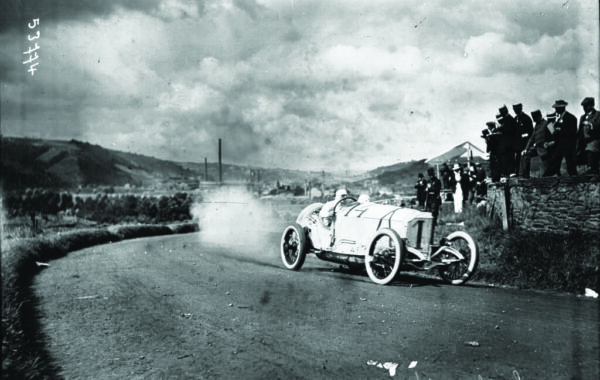

Hosted by the L’Automobile Club de France, it was the 1914 French Grand Prix. Held over 7 hours and 753km of back-breaking roads through the French countryside, it was the biggest race of

the Grand Prix season. France had already cemented itself as the hub of European motorsport and the dominant cars in the field were the Peugeots with their double overhead cam engines and

four-wheel brakes.

Peugeot also had a strong team of drivers which included the great Georges Boillot. The moustachioed French racer already had many Grand Prix wins under his belt and many would expect him to have repeated success in his home Grand Prix. However, another manufacturer had

other plans.

Mercedes had stayed out of Grand Prix racing since 1908 after a win in that year’s French Grand Prix. Daimler-Benz management decided to focus on the production on aircraft engines instead. This field allowed the Germans to gain a unique understanding of lightweight materials and design. This is something which proved invaluable for readying a fleet of five cars for the 1914 Grand

Prix season.

With the assassination of Austria-Hungary Archduke Franz Ferdinand occurring only a week before, and the potential for war breaking out between the European powers growing ever stronger, Daimler-Benz decided, for political reasons, that Mercedes must win the French Grand Prix that year.

The tool to do it was the Mercedes 18/100. It featured a 4.5L four-cylinder engine based on an aircraft design with four valves per cylinder. Each cylinder was built from forged steel instead of cast iron. Each 18/100 weighed in at 1100kg with power rated at 78kW and 283Nm

of torque.

The 18/100 was also good for 112mph flat out. Mercedes, also keen to promote the German alliance with Austria-Hungary, stated their new car’s crankshaft was built with high-grade Austrian steel. However, the Mercedes did not feature the same four-wheel brakes as the Peugeot. This would give Peugeot a tremendous advantage in the corners, but Mercedes had their star driver, Christian Lautenschlager. Having won the Grand Prix in 1908, Lautenschlager was highly skilled and would be a great asset.

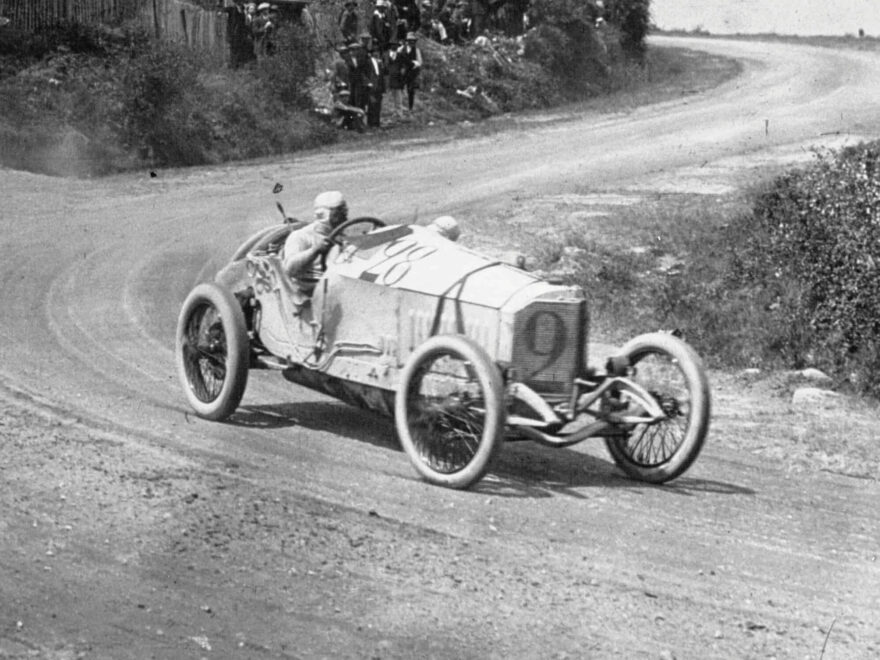

At 8am on July 4th, 37 cars from six countries all took their place for the start. The 20 lap French Grand Prix got underway with two cars setting off at 30-second intervals. Boillot took an early lead, but the Mercedes of German, Max Sailer managed to pass him when the Frenchman pitted unexpectedly after

the first hour.

Despite not having the edge in stopping power, the Mercedes was just as composed in the corners and much quicker than the Peugeots on the straights.Sailer pushed hard and set a new lap record on the fourth lap. He was inexperienced and keen to show Lautenschlager he was capable in the seat.

However, Sailer retired after pushing his car too hard on lap six. As a result of this, and the other hard-driven Mercedes of Theodore Pillette retiring as well, much of the field also dropped out due to pressure from the Germans. Some claim team Mercedes used these two as “rabbit” cars to break the field, but all involved on the day have denied this was the case.

That said, Mercedes ran their team with military-like precision. They knew exactly where each car was in the race at any given time. As more cars dropped out to due to mechanical problems,

Mercedes slowly moved their faster cars up into position.

Boillot in his Peugeot managed to keep a commanding lead until the 12th lap where Lautenschlager in his Mercedes managed to pass him. The lead was now see-sawing between Lautenschlager and Boillot. The crowds went ballistic every time they passed the start/finish line, as the end of each lap saw a different leader.

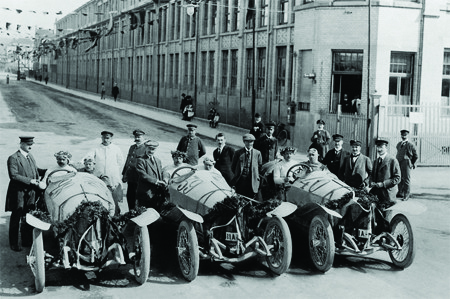

After a heroic drive, Boillot over revved his Peugeot and retired with just two laps to go. He sat on the side of the road weeping. With the pressure from Peugeot off, Lautenschlager eased off and led two other Mercedes to an historic 1-2-3 victory. Peugeot and the 300,000 French fans were utterly stunned.

Mercedes had emerged triumphant. However, just three weeks after their win, Europe was plunged into conflict. The First World War had begun.

Christian Lautenschlager’s winning Mercedes 18/100 still exists today in the hands of a private collector. Lautenschlager would return to racing in the years after World War One. He even drove for Mercedes in the Indy 500, but with limited success. Boillot served as a fighter pilot during the war. Sadly, he was tragically killed in 1916 after being shot down over Verdun.

Mercedes would go on to turn Grand Prix racing upside down in the 1930s. However, their exploits with fellow German team Auto Union are for another story entirely.